Who prepares the toughest brick paver bases in the Fox Cities?

Stonehenge does, of course!

And we’re willing to bet that every other hardscape contractor in Wisconsin that you’d ask would give you the same answer.

So how can we say with any authority that ours is best?

We do more than just read trade magazines and talk to mfg reps. We test. Side-by-side, head to head, we test our materials and methods against the other methods and materials out there. And because brick paver patios are among our bread and better offerings, we absolutely had to be sure we were offering our clients in Appleton, Neenah, Menasha and the rest of the Valley the very best, most durable paver installations.

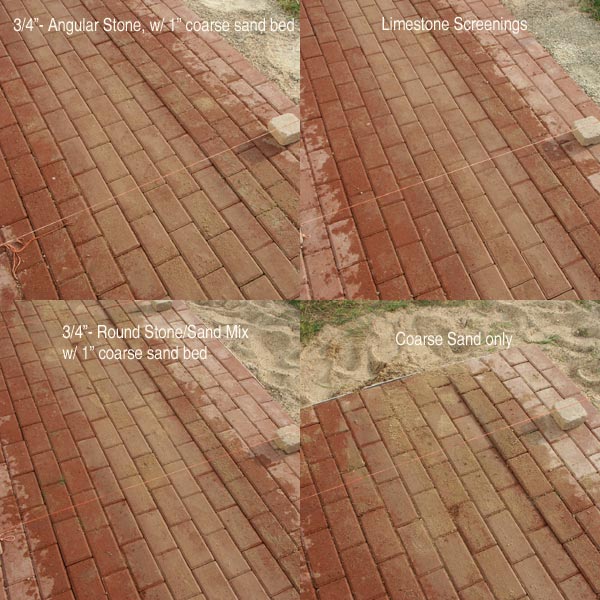

So a few years back we tested all of the available methods and stone types available to us for use as patio base. We excavated an area behind our shop and prepared four different sub-bases to test in that space. The base preparations were as follows:

- 6″ of “crusher run” limestone (also called “three-quarter minus”, to indicate stone sizes of 3/4″ down to fine dust) topped with 1″ of coarse sand. This material and method are often touted as being the best, but anecdotal evidence we had showed that not to be true.

- 7″ of “screenings”, which is crushed limestone of sizes 3/8″ down to fine dust. (Of note, we are picky about where we source our screenings from – most suppliers in the area offer screenings with stone sizes that are too small, giving poor interlock. For this test we used our favorite supplier.)

- 6″ of “road base”, an aggregate material mix found mainly in northern parts of Wisconsin and used as the base for most pavements there. It’s composed of rounded granite stones of approx 3/4″ mixed with a very coarse, slightly loamy sand. 1″ of coarse bedding sand topped this sub-base as well.

- 7″ of coarse sand. Occasionally we hear about people using this as the sole material for a base. We knew full well this would not hold up as a base, but we wanted empirical evidence showing how poorly it would serve beneath a flexible pavement like brick pavers.

The test: We applied equal compaction to each base, screeded each to the exact same slope. We then installed pavers over the area using the weakest interlocking pattern known; running bond. The objective was to make the conditions least optimal for these bases and the pavement, and then to force failure to see which would hold up the longest.

To force failure, we sprayed an equal amount of water over each pavement, and then immediately drove a small vibratory compactor in a straight line across all four areas. The water acts as a lubricant, allowing stone particles to shift when forces are applied to them. The same thing happens when you walk on your patio during or after a rain.

We performed many iterations of spray-and-compact to provide years worth of wear in a single afternoon, until we had clear winners and losers.

The winner? The base preparation method we’d been using all along, which was 7″ of screenings. It showed the least amount of settling and displacement post-compaction. Second place was the base that used 6″ of crusher run and an inch of sand.

Not Resting On Our Paver Laurels

The fact that our preparation method won the test was nice, but it didn’t mean there weren’t lessons to be learned and changes to be made in how we prepare the foundation of the paver projects we install across the Fox River Valley. The reason the sand-over-stone base preparations failed earlier is because of the sand. Coarse or not, sand particles are just not large enough to resist moving when forces are applied to them. Ever walk barefoot on a beach? Where does the sand go? Between your toes, right?

The crushed stone beneath that sand is solid. Unmoving when the force of feet or small vehicles are applied to it. And when it comes to force resistance and strength of interlock, large angular stone trump small angular stone every time. So the sub-base of the crusher base preparation was stronger than that of the screenings base preparation, but made weaker overall by the sand bedding course on top of it.

From that test we changed how we installed our pavements, taking the best of these top two methodologies to create a “Superbase”: Crusher run sub-base under a screenings upper base. The result is something stronger than anything any of our competitors are installing in our area.

"With Stonehenge you get a company that's rich in experience and large enough to tackle any project you could possibly throw at us, but small enough that you'll see the same faces throughout your entire experience. " - Jeff Pozniak, President

"With Stonehenge you get a company that's rich in experience and large enough to tackle any project you could possibly throw at us, but small enough that you'll see the same faces throughout your entire experience. " - Jeff Pozniak, President